Cambridge (1973-77)

The first in the Cambridge calculator range, this model can be recognised by its “C” clear key and separate “K” constant key. It featured a red eight-digit LED display and weighed under 100 grams—small even by today’s standards and among the lightest pocket calculators then available. Buyers could choose between a more expensive ready-made unit or a kit for home assembly. It was initially priced at around a week’s average wages, though prices fell sharply within two years. The Cambridge line later grew to include many variations.

This compact brown calculator was part of Sinclair’s second major calculator series, designed to be light, low-cost, and easy to assemble. It offered basic arithmetic functions and replaced the “K” constant key—used to repeat a number in successive calculations—with automatic constants on all operations. A clear entry “CE” key was also added, allowing users correct the most recent digit without starting over. Introduced just a year after the Executive, the Cambridge range was sold fully assembled or as a DIY electronics kit for home assembly.

This model in the Cambridge range combined a constant key “K” with a dual-function clear key “CE”—one press erased the last entry, two presses cleared the entire calculation. It featured an easy to read red LED display, ran on four AAA batteries, and was powered by a General Instruments chip. Like other Sinclair calculators, it was sold pre-assembled or as a DIY kit, often advertised for mail order. It remained compact and lightweight, weighing under 100 grams.

This early memory model introduced a basic memory function to Sinclair’s four-function Cambridge calculator. This allowed users to store a number during a calculation and retrieve it later — useful for working with running totals or repeated values. Its black casing, powered by four AAA batteries, housed a General Instruments processor and an eight-digit red LED display. Available fully built or as a kit, the Type 1 remained compact and convenient for home or classroom use.

This later variation of the Cambridge calculator introduced a percentage key—simplifying calculations for sales, tax, or interest—alongside separate clear “C” and clear-entry keys “CE”—offering more flexibility for everyday calculations. It retained the eight-digit LED display of earlier models but ran on just two AAA batteries, making it lighter than previous versions. By the time this model was released, the price of Cambridge calculators had dropped to a fifth of their original cost—part of Sinclair’s push to make electronic calculators affordable for a mass market.

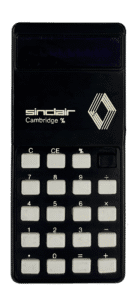

This version of the Cambridge calculator was made in Spain and appears technically identical to the Type 4 model, with a percentage key alongside separate clear “C” and clear-entry “CE” keys, but features a different label—possibly to emphasise its % function. It was likely produced as part of a promotional campaign branded for the car manufacturer Renault. In the 1970s, calculators were increasingly used as corporate gifts, reflecting a broader trend in branded technology and lifestyle merchandising. This object illustrates how consumer electronics also became tools of marketing and brand identity.

This silver-toned model expanded on the original Cambridge Memory by adding a percentage key. It used the same processor as Type 1 but required only two AAA batteries, making it lighter and more compact. Its combination of memory and percentage functions aimed to support more flexible everyday use, while preserving the LED display and pocketable form. However, users sometimes found it hard to switch off—a common fault caused by oxidation in the tin-coated switch contacts, used instead of more reliable gold-plated parts.

This particular example combines features of two Cambridge models. Although functionally a Type 2 model, with a percentage key, memory functions, and two-AAA power supply, this calculator shares the black casing and red LED display of the earlier Type 1. Its blue and grey keys provide the familiar Sinclair layout for basic arithmetic, percentage, and stored values. A thin white line appears above the Sinclair logo—an unusual feature not seen on other known examples. The name “Gordon Smith” was once inscribed on the exterior and remains etched inside the case’s battery cover. Such personalisation hints at the calculator’s individual history alongside its mass-produced origins.

This late addition to the Cambridge range allowed users to write and store short programmes using a 36-step memory. It supported memory storage, brackets, and conditional jumps—advanced features for a calculator of its size and price. The model was supplied with a booklet of examples, and users could also buy a library of 294 additional programmes, published in four booklets. Powered by a single PP3 battery, it featured an enlarged rear casing that could make the calculator wobble on flat surfaces—a design also seen in a few other Cambridge models.

This calculator is functionally identical to the Sinclair Cambridge Programmable but feature the logo of American electronics chain Radio Shack. It included 36 programmable steps, memory, brackets, and branching instructions—features rarely found at this price point. While visually nearly indistinguishable, including its white plastic case, from Sinclair’s model, its branding reflects how programmable calculators began reaching broader international markets through major retail distributors.

Housed in bright red plastic, this was the most distinctive of the Cambridge Memory models. Type 3 introduced a revised keyboard layout with memory “M” and dual-function clear “C/CE” keys. Unlike earlier Cambridge models that used AAA batteries, this version was powered by a 9-volt PP3 battery, which required a bulging rear casing—earning it the nickname “pregnant” model. It featured a Mostek integrated circuit and red LED display. By the mid-1970s, features like memory and percentage functions were becoming standard, even in budget pocket calculators.

This model marked a shift in the Cambridge range, offering functions for scientific and engineering use—not just basic arithmetic. It could handle angles in degrees or radians, display results in scientific or standard notation, and store values in memory. The bright LED screen displayed up to eight digits, powered by two AA batteries. At the time, its relatively low cost made it an attractive option for students and professionals looking for an affordable, pocket-sized scientific calculator

This expanded model in the Cambridge range added square root, square, percentage, and memory functions to the standard four. Like some other Sinclair calculators, it used a 9-volt (PP3) battery housed in a raised rear compartment. This protruding cover made the device less stable on flat surfaces, often causing it to wobble when pressed. With a red LED display and white plastic body, the Universal reflected Sinclair’s effort to offer more features in the original range at a time of falling prices and growing competition.

This version of the Cambridge Universal calculator appears identical in function and design, but features Plessey branding—a likely promotional collaboration. Plessey, a major British electronics company, had early ties to Clive Sinclair, who used their discarded transistors in his early hi-fi kits. By the late 1970s, promotional calculators were widely used as branded corporate gifts. This object highlights how Sinclair’s products served both consumer and marketing roles in a rapidly evolving electronics landscape.